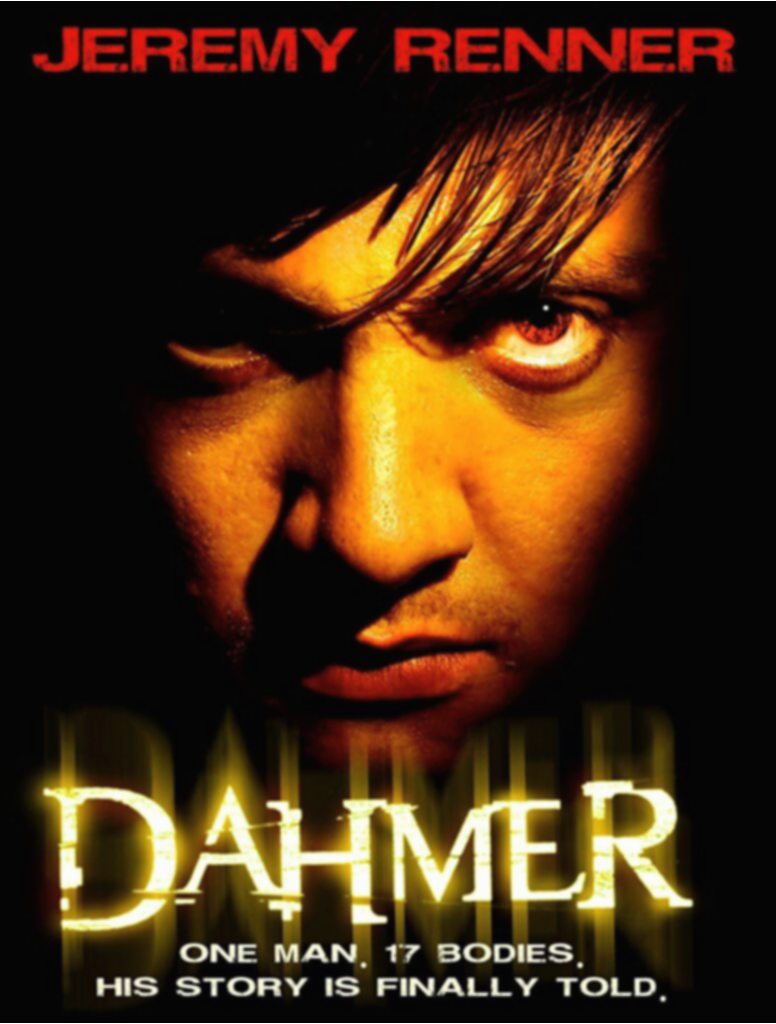

DAHMER

WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY DAVID JACOBSON

DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT

Jeffrey Dahmer was born in 1960. He died in 1994, beaten to death in a prison bathroom where he was serving out a life sentence. During his short lifetime, Dahmer gained notoriety for killing seventeen men, using them in bizarre sexual rituals, and cannibalizing parts of their bodies. It has been said that the name Jeffrey Dahmer is better known in the United States than several recent presidents, yet little is known of the emotionally significant and intellectually intriguing story that lies behind the headlines.

Dahmer drugged his victims and after they passed out, he strangled them. His primary goal was not to make them suffer or to kill them, but to make them his own. He wanted his lovers to be completely under his control. When he cannibalized them, he claimed he did so in order to “take them inside of himself” where he could “keep them forever”. He didn’t kill to get rid of people; he killed to keep people with him. He killed for companionship. That is the tragic irony at the center of this story, an emotional drama about risks everyone struggles with. It is about the dance we must all perform between being connected with others and being free to act out our own willful aims.

Though it is based on a true crime story, The Mind is a Place of its Own is neither a conventional biopic, nor another serial killer genre film. It focuses on a few chosen moments from Dahmer’s life — the times leading up to his first murder, when he was a High School senior, and then some years later after he had killed most of his victims. Instead of a catalogue of gory crimes, the film attempts to show what lead up to the crimes. It is still a suspenseful tale about a killer, but the emphasis is on the emotional and psychological life of the character.

In Fritz Lang’s “M”, a child molester is chased down by an outraged mob. He has committed crimes even most criminals won’t accept. Yet at the end of this film the terrifying killer is shown to be weak, tortured, and pathetic. Clearly he was as much prey to his own uncontrollable impulses as his victims had been prey to him. In a shocking turnaround, he becomes sympathetic, but it is more than just a twist. It is a huge strike for humanity. To see any human being as an incomprehensible symbol of evil, in effect, an unwanted thing to be eliminated, is to add evil to evil. Ultimately, The Mind is a Place of its Own is an attempt to comprehend Jeffrey Dahmer, a real-life symbol of evil, and in so doing, broaden our sense of what it is to be human.

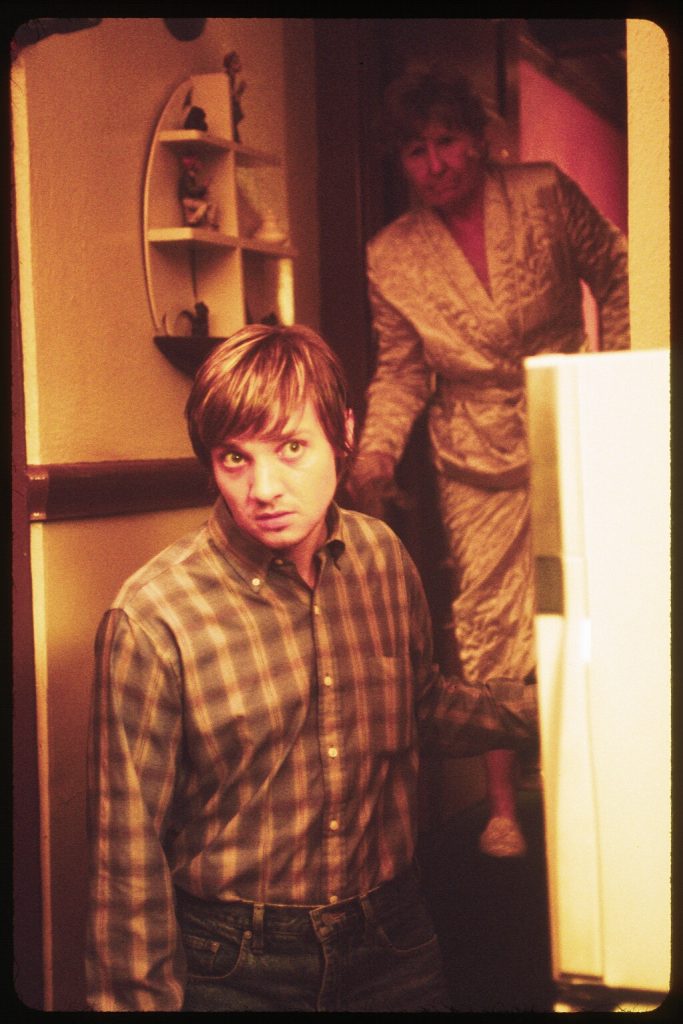

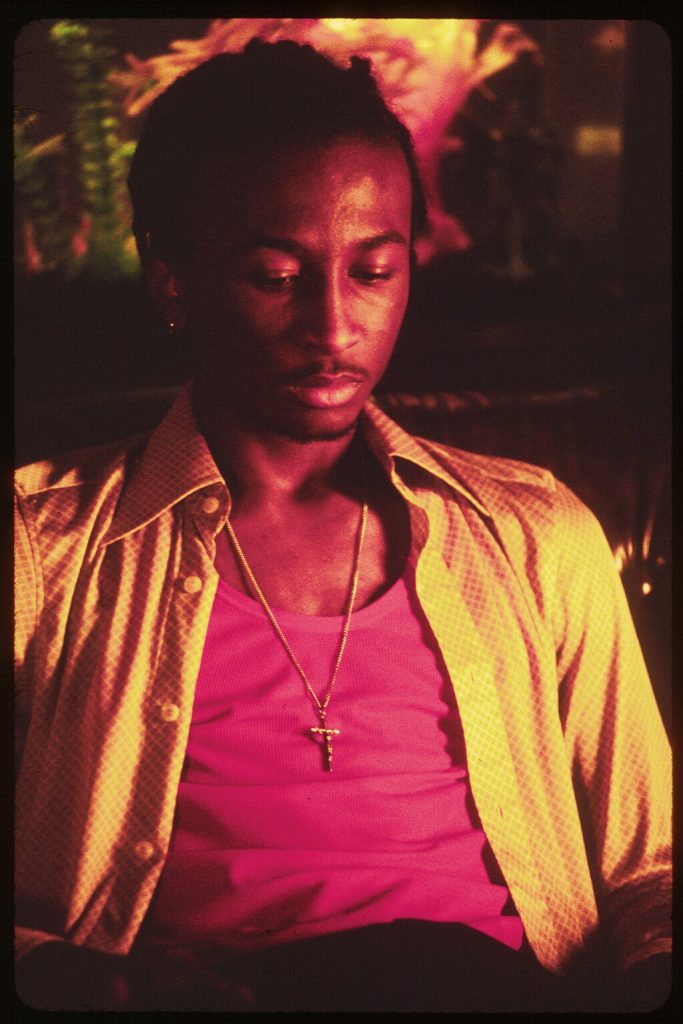

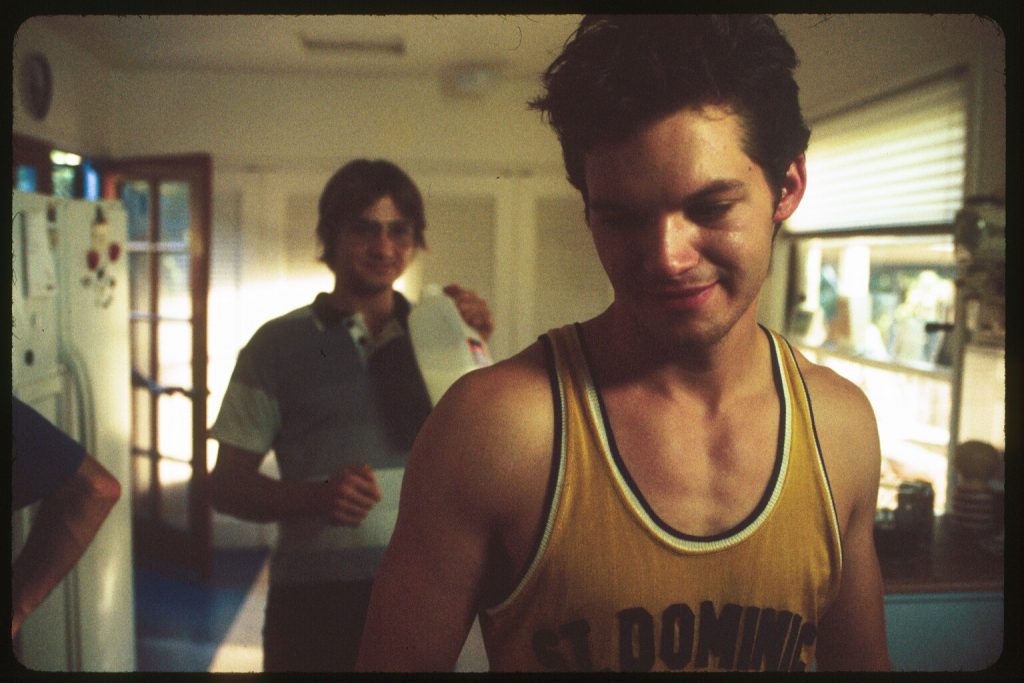

Jeremy Renner and Dion Basco

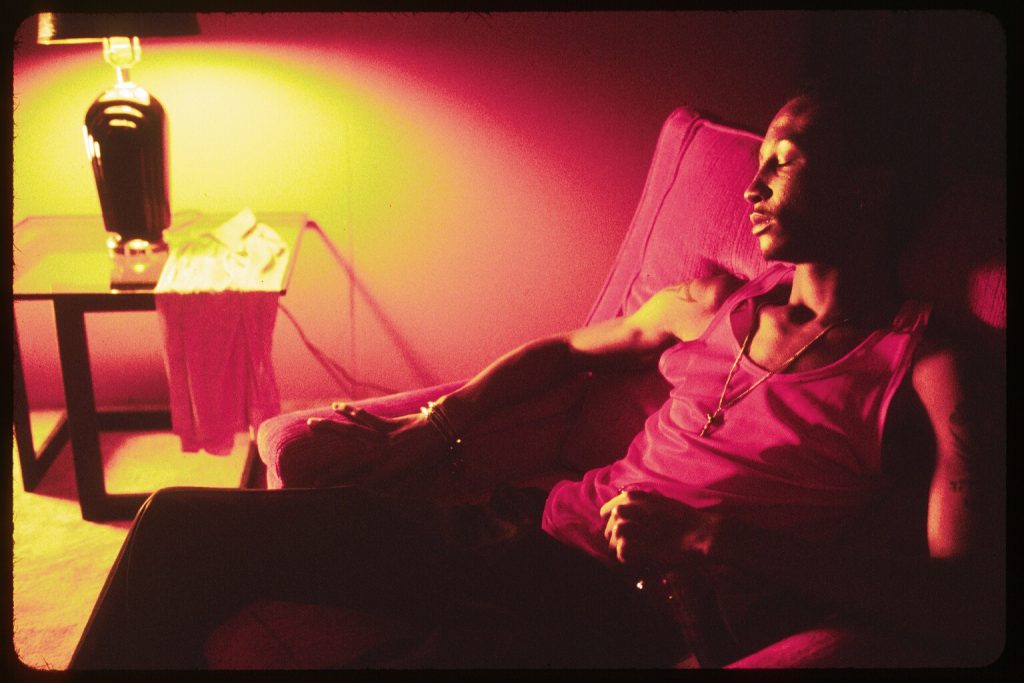

Jeremy Renner and Dion Basco

REVIEWS

David Jacobson, who enjoyed acclaim with features “Criminal” and “Roast Suckling,” is a writer-director worthy of serious attention. Throughout “Dahmer,” he displays a consistently confident approach, with a strong belief that the camera can show the surface layer of people, things and actions, and allow for meaning to gradually seep through. Pic is as interesting for what it leaves out as for what it keeps in, and most impressive of all is the absence of a moralistic perspective on the killing rampage that reached its climax in 1991. It is quite enough, the film suggests, to show and not tell, albeit in a form that accordions and slightly fictionalizes the numerous deaths, fluidly interspersed with flashbacks.

Opening credit montage of assembly line at chocolate factory where Dahmer works in the early ’90s immediately tells viewer that this isn’t the Jeffrey Dahmer movie anyone is expecting, and with calm, precise efficiency, action moves right into Dahmer bringing a victim, Khamtay (Dion Basco), home for slow torture. Incredibly, Khamtay manages to get away, but Dahmer convinces skeptical Milwaukee cops that he’s just a friend who’s a bit out of it.

Not only does this sequence, shorn of all but the most essential talk, show how Dahmer managed to get away with his killings for several years, but it artfully places the viewer in a third-person position to observe such incidental but chilling shocks as Khamtay reviving in bed and finding the corpse of a black man beside him, or Dahmer going to his grandma’s house to dispose of a crow which has gotten inside her kitchen.

This interlude, driven by light strobes and rapid montage, is the only one with a hint of sensationalism. Otherwise, pic is almost startlingly matter-of-fact, supported by a keen sense of gradual build-up. Slow burn is beautifully handled in another flashback, which is punctuated by repeat visits to present, showing Dahmer’s first killing when he was still living at home. Murder of Lance Bell (Matt Newton) is an act which startles Dahmer as much as his victim, and it’s here that Renner’s quiet characterization reaches full depth.

Thus begins a series of flashbacks that may be too numerous for the movie’s own good, but which fill in the details of this human monster. An extremely effective and sustained scene with a younger Dahmer trying to hide his growing fetishes for mannequins from grandma (Kate Williamson) and Dahmer’s inquisitive father Lionel (Bruce Davison) encapsulates the growing up stage and the faulty family life in a few minutes. Another flashback is triggered by Dahmer picking up young, cocky Rodney (Artel Kayaru) in a knife store and going to a gay bar where, a few years before, Dahmer had systematically drugged and raped dozens of male clubbers.

A flat, slightly overfed and sleepy Mid-western style informs Renner’s Dahmer. It’s a brave performance on every level, not only in the occasionally graphic displays of savagery but in a deliberate blankness that covers his character like a scum. Davison as Dahmer’s father gives off glints of suspicion, but, like everyone else, nary a grasp of the scale of the depravity before him. Karayu, Basco and Newton as the black, Asian and white victims suggest Dahmer’s perhaps unconscious wish to slaughter the human race.

Pic’s look is a vibrant, hard modernism of a refined sort, with the camera usually kept at a distance. The exquisite soundtrack pulsates with selected sounds conveying (sans images) violence and an electronic score of unnerving moodiness by Christina Agamanolis, Marianna Bernoski and Willow Williamson.

–Robert Koehler, Variety

OVER AND OVER AGAIN in this haunting film based on the life of yet another Wisconsin serial killer, Jeffrey Dahmer (Jeremy Renner), with a look of fascination on his face, places his ear against the rib cage of the young man he’s just murdered, straining to hear . . . something. But what, exactly? The heart’s fading beat or the sound the soul makes as it departs the body?

Writer-director David Jacobson doesn’t know the answer any more than we do, but he’s drawn to the intimacy of such scenes, which, by all accounts, were the only times Jeffrey was able to relax around another person and be, heaven help us, himself. Jacobson must be a bit mad as well to take on such a reviled figure, but he’s canny about it, re-configuring Dahmer’s real-life timeline to catch him in what might be termed his middle period, before the unimaginable (and unfilmable) formaldehyde vats and refrigerated body parts. Here, there are two corpses in the bedroom of Jeffrey’s otherwise pristine Milwaukee apartment, while in the living room there’s Rodney (Artel Kayàru, in a virtuoso performance), the lithe, love-starved young African-American man Dahmer has picked up in a sporting-goods store, who won’t sit still and won’t stop talking, despite the sleeping pills Dahmer has slipped into his whiskey and Coke.

Zoning out on the chatter, Jeffrey in his mind travels back in time to his teenage years and impromptu first murder, then to a Sunday morning before church when his father, played with exquisite restraint by Bruce Davison, demanded to see what was stored in the old wooden box in the back of Jeffrey’s closet.

As Lionel Dahmer’s heartbreaking memoir A Father’s Story, makes clear, it would be years before he learned what his son was preserving in there, but Jacobson has turned that Sunday-morning encounter into a weirdly suspenseful — and beautifully acted — scene. Watching it raises conflicting feelings, for we pretty much know the nature of the box’s contents (something gruesome), and while we yearn for Dad to discover the truth — and thereby save all of Jeffrey’s future victims —

there’s also a deeply ingrained movie instinct that kicks in at the same time, the one that desires the bad guy to get away with it, if only for a while longer.

Back within Apartment 213’s red- and orange-painted walls, Jeffrey is in control, relaxing in his armchair, guzzling whiskey and chain-smoking with all the imperiousness of a boulevard queen. He’s unflappable on the surface, but Renner, who is extraordinary, holds in his eyes everything the director’s flashbacks have shown us about Jeffrey’s career track, from the novice who wept wrenchingly after his first kill, to the sadist who calmly drilled a hole in the head of the young man (Dion Basco) lying in the bedroom five paces away.

The drill, the saw, the acid — Jacobson doesn’t linger over them, which makes it all the more devastating when, near film’s end, he re-creates an act of bodily transgression on Dahmer’s part that is shocking and yet so dreamlike that it may not hit you until the drive home. More disturbing is that the moment feels apt, as if such depravity were part of a natural progression of events — which makes this the purest of horror films. Its subtitle is “The Mind Is a Place of Its Own,” and in such a realm, transgression isn’t a step the transgressor pauses over, but one composed of inevitability, forward motion, and a complete absence of doubt and regret.

— Chuck Wilson, LA Weekly